Evaluating the use of Monoclonal Antibodies - Sotrovimab, Casirivimab/Imedvimab (REGEN-COV) and Tixagevimab/Cilgavimab (EVUSHELD) for COVID-19 Treatment in Singapore

et al., Open Forum Infectious Diseases, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofae631.2172, Jan 2025

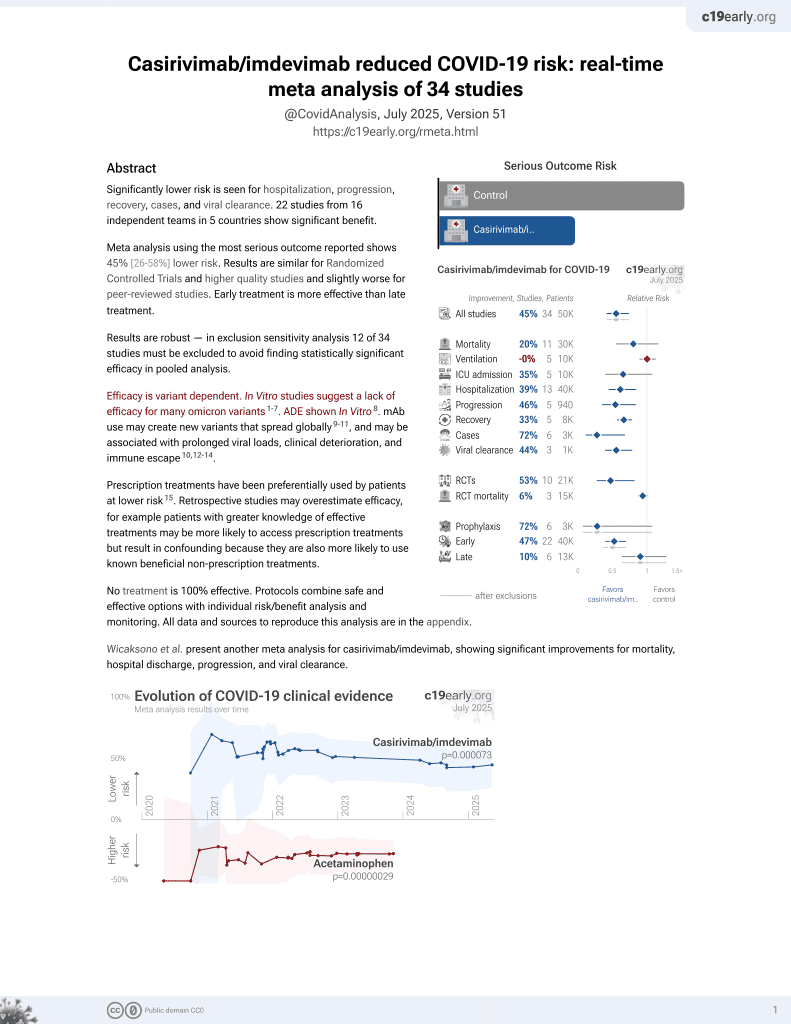

19th treatment shown to reduce risk in

March 2021, now with p = 0.000095 from 34 studies, recognized in 52 countries.

Efficacy is variant dependent.

No treatment is 100% effective. Protocols

combine treatments.

6,400+ studies for

210+ treatments. c19early.org

|

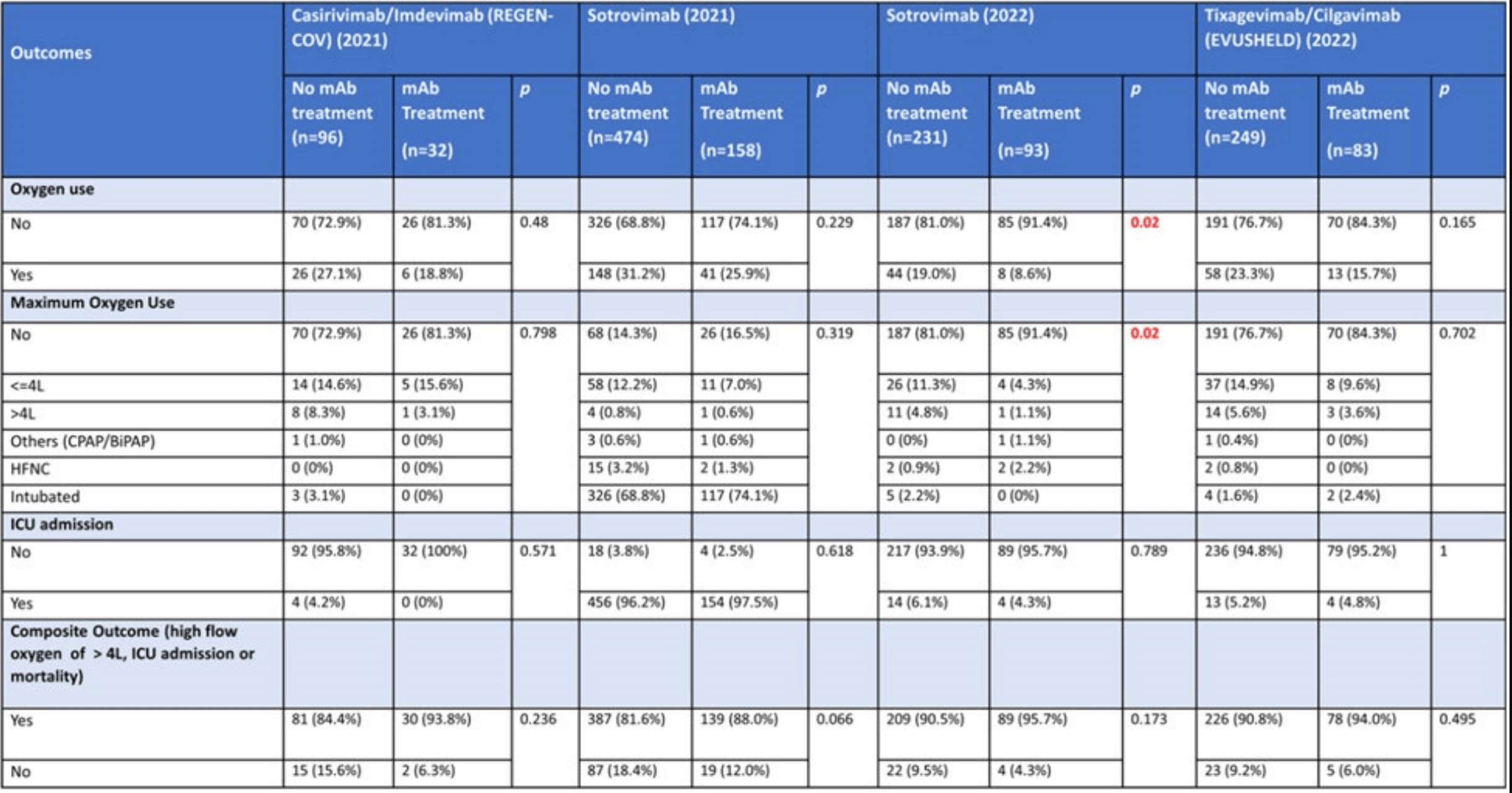

PSM retrospective 366 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Singapore showing no statistically significant reduction in severe outcomes with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), except for lower oxygen use in patients treated with sotrovimab during the Omicron wave. The 2021 numbers for sotrovimab do not appear to be reported correctly, for example showing >96% intubation and higher incidence of ICU admission than the composite outcome that includes ICU admission. Multiple numbers appear to have been transposed.

Efficacy is variant dependent. In Vitro research suggests a lack of efficacy for many omicron variants1-7.

Study covers sotrovimab, casirivimab/imdevimab, and tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

|

risk of mechanical ventilation, 80.0% lower, RR 0.20, p = 0.57, treatment 0 of 32 (0.0%), control 3 of 96 (3.1%), NNT 32, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm), propensity score matching.

|

|

risk of ICU admission, 84.2% lower, RR 0.16, p = 0.57, treatment 0 of 32 (0.0%), control 4 of 96 (4.2%), NNT 24, relative risk is not 0 because of continuity correction due to zero events (with reciprocal of the contrasting arm), propensity score matching.

|

|

risk of oxygen therapy, 30.8% lower, RR 0.69, p = 0.48, treatment 6 of 32 (18.8%), control 26 of 96 (27.1%), NNT 12, propensity score matching.

|

| Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules prioritizing more serious outcomes. Submit updates |

1.

Liu et al., Striking Antibody Evasion Manifested by the Omicron Variant of SARS-CoV-2, bioRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.12.14.472719.

2.

Sheward et al., Variable loss of antibody potency against SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron), bioRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.12.19.473354.

3.

VanBlargan et al., An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron virus escapes neutralization by several therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, bioRxiv, doi:10.1101/2021.12.15.472828.

4.

Tatham et al., Lack of Ronapreve (REGN-CoV; casirivimab and imdevimab) virological efficacy against the SARS-CoV 2 Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) in K18-hACE2 mice, bioRxiv, doi:10.1101/2022.01.23.477397.

5.

Pochtovyi et al., In Vitro Efficacy of Antivirals and Monoclonal Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Lineages XBB.1.9.1, XBB.1.9.3, XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16, XBB.2.4, BQ.1.1.45, CH.1.1, and CL.1, Vaccines, doi:10.3390/vaccines11101533.

Chua et al., 29 Jan 2025, retrospective, Singapore, peer-reviewed, 9 authors.

Evaluating the use of Monoclonal Antibodies -Sotrovimab, Casirivimab/ Imedvimab (REGEN-COV) and Tixagevimab/Cilgavimab (EVUSHELD) for COVID-19 Treatment in Singapore

Identifying patients at higher risk for developing severe COVID-19-related complications (69%) • Incorporating new information about treatment options for non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (67%) • Ensure patients receive treatment within the appropriate therapeutic window (60%) • Educating patients on COVID-19 and available antiviral treatments (58%) • Screening patients for potential DDIs prior to COVID-19 antiviral initiation (55%) • Some of the barriers to implementing these practice changes include: • Patients present outside the recommended treatment window • Unfamiliar with potential drug-drug interactions for COVID-19 antivirals • Patient concerns or questions regarding available antivirals • Unfamiliar with guideline recommendations for available antivirals • Lack of time during office visits to educate patients on the importance of timely testing and treatment

chua