Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Prior to Infection and Risk of Post–COVID-19 Condition

et al., JAMA Internal Medicine, doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6555, Feb 2023

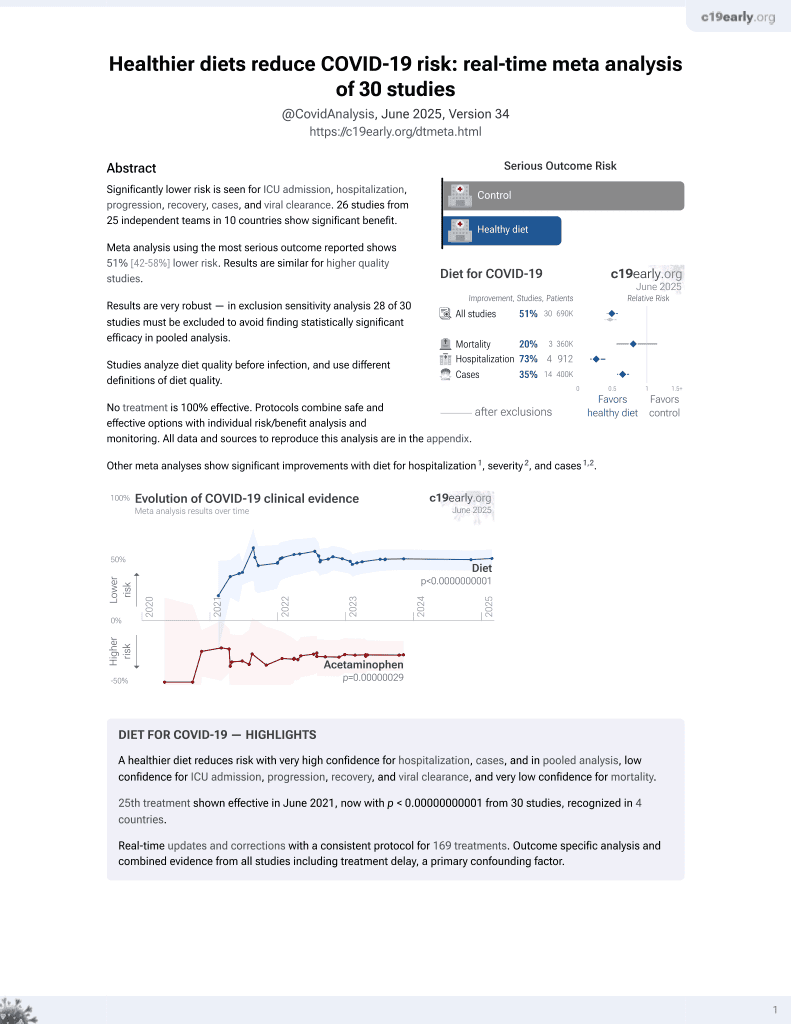

Diet for COVID-19

26th treatment shown to reduce risk in

June 2021, now with p < 0.00000000001 from 30 studies, recognized in 4 countries.

No treatment is 100% effective. Protocols

combine treatments.

6,400+ studies for

210+ treatments. c19early.org

|

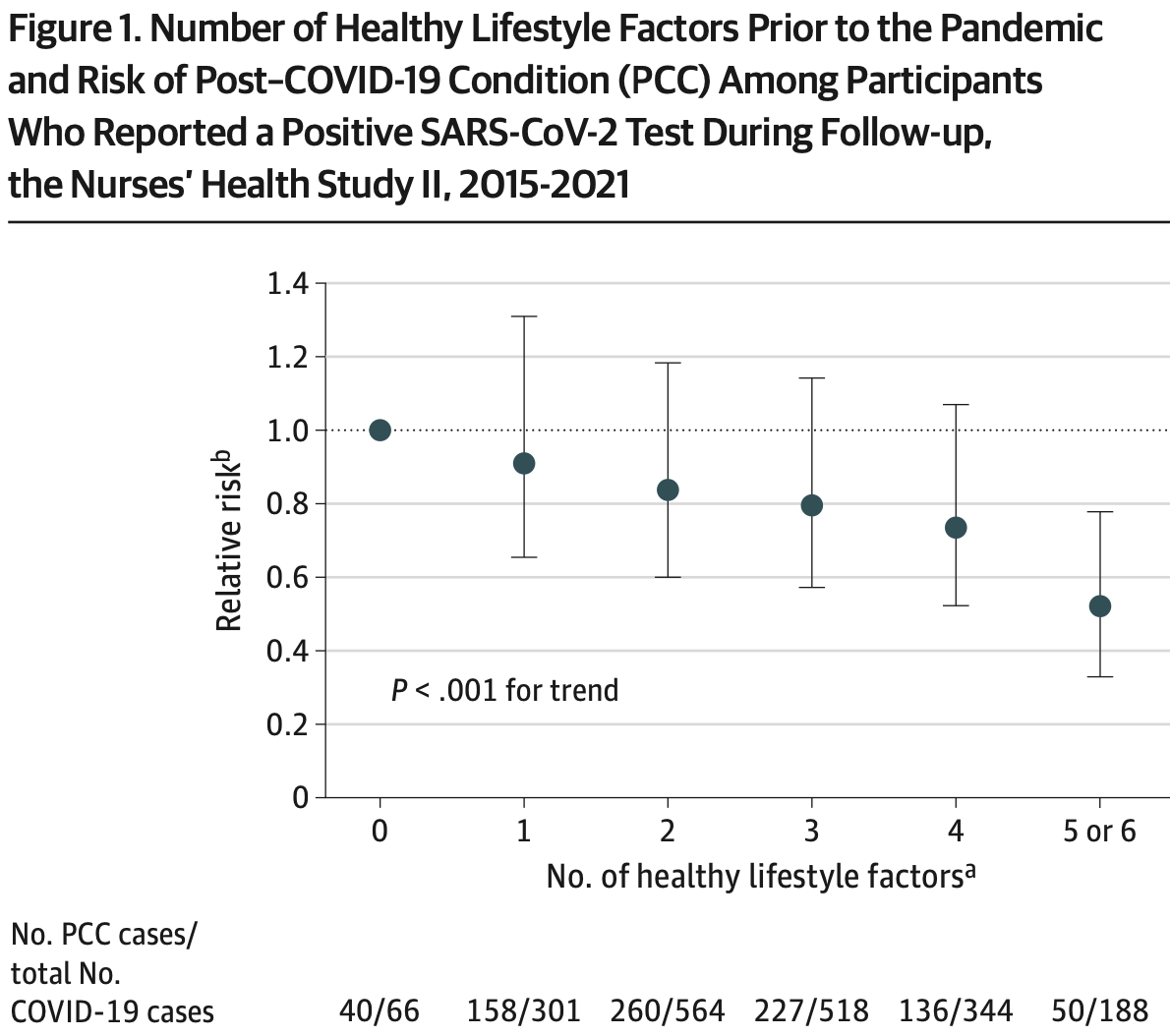

Prospective analysis of 32,249 women from the Nurses’ Health Study II in the USA, showing lower risk of PASC with a healthy lifestyle, and in a dose-dependent manner. Participants with 5 or 6 healthy lifestyle factors had significantly lower COVID-19 hospitalization and PASC. BMI and sleep were independently associated with risk of PASC.

Standard of Care (SOC) for COVID-19 in the study country,

the USA, is very poor with very low average efficacy for approved treatments1.

Only expensive, high-profit treatments were approved for early treatment. Low-cost treatments were excluded, reducing the probability of early treatment due to access and cost barriers, and eliminating complementary and synergistic benefits seen with many low-cost treatments.

|

risk of long COVID, 9.0% lower, RR 0.91, p = 0.43, higher quality diet 124 of 318 (39.0%), lower quality diet 218 of 480 (45.4%), NNT 16, adjusted per study, Q5 vs. Q1, multivariable, model 2.

|

|

risk of long COVID, 49.0% lower, RR 0.51, p = 0.002, higher quality diet 188, lower quality diet 66, 5 or 6 healthy lifestyle factors vs. 0.

|

|

risk of hospitalization, 78.1% lower, RR 0.22, p = 0.006, higher quality diet 5 of 188 (2.7%), lower quality diet 8 of 66 (12.1%), NNT 11, 5 or 6 healthy lifestyle factors vs. 0.

|

| Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules prioritizing more serious outcomes. Submit updates |

Wang et al., 6 Feb 2023, prospective, USA, peer-reviewed, survey, mean age 64.7, 8 authors, study period April 2020 - November 2021.

Contact: siwenwang@hsph.harvard.

Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Prior to Infection and Risk of Post–COVID-19 Condition

JAMA Internal Medicine, doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6555

Few modifiable risk factors for post-COVID-19 condition (PCC) have been identified. OBJECTIVE To investigate the association between healthy lifestyle factors prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of PCC.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS In this prospective cohort study, 32 249 women in the Nurses' Health Study II cohort reported preinfection lifestyle habits in 2015 and 2017. Healthy lifestyle factors included healthy body mass index (BMI, 18.5-24.9; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), never smoking, at least 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity, moderate alcohol intake (5 to 15 g/d), high diet quality (upper 40% of Alternate Healthy Eating Index-2010 score), and adequate sleep (7 to 9 h/d). MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES SARS-CoV-2 infection (confirmed by test) and PCC (at least 4 weeks of symptoms) were self-reported on 7 periodic surveys administered from April 2020 to November 2021. Among participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the relative risk (RR) of PCC in association with the number of healthy lifestyle factors (0 to 6) was estimated using Poisson regression and adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities. RESULTS A total of 1981 women with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test over 19 months of follow-up were documented. Among those participants, mean age was 64.7 years (SD, 4.6; range, 55-75); 97.4% (n = 1929) were White; and 42.8% (n = 848) were active health care workers. Among these, 871 (44.0%) developed PCC. Healthy lifestyle was associated with lower risk of PCC in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with women without any healthy lifestyle factors, those with 5 to 6 had 49% lower risk (RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.33-0.78) of PCC. In a model mutually adjusted for all lifestyle factors, BMI and sleep were independently associated with risk of PCC (BMI, 18.5-24.9 vs others, RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-1.00, P = .046; sleep, 7-9 h/d vs others, RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.95, P = .008). If these associations were causal, 36.0% of PCC cases would have been prevented if all participants had 5 to 6 healthy lifestyle factors (population attributable risk percentage, 36.0%; 95% CI, 14.1%-52.7%). Results were comparable when PCC was defined as symptoms of at least 2-month duration or having ongoing symptoms at the time of PCC assessment.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE In this prospective cohort study, pre-infection healthy lifestyle was associated with a substantially lower risk of PCC. Future research should investigate whether lifestyle interventions may reduce risk of developing PCC or mitigate symptoms among individuals with PCC or possibly other postinfection syndromes.

References

Ahmadi, Huang, Inan-Eroglu, Hamer, Stamatakis, Lifestyle risk factors and infectious disease mortality, including COVID-19, among middle aged and older adults: evidence from a community-based cohort study in the United Kingdom, Brain Behav Immun, doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.022

Akbaraly, Shipley, Ferrie, Long-term adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and chronic inflammation in the prospective Whitehall II study, Am J Med, doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.002

Al-Delaimy, Willett, Measurement of tobacco smoke exposure: comparison of toenail nicotine biomarkers and self-reports, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2695

Aldabal, Bahammam, Metabolic, endocrine, and immune consequences of sleep deprivation, Open Respir Med J, doi:10.2174/1874306401105010031

Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin, Steves, Risk of long COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2, Lancet, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00941-2

Azzolini, Levi, Sarti, Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and long COVID after infections not requiring hospitalization in health care workers, JAMA, doi:10.1001/jama.2022.11691?utm_campaign=articlePDF%26utm_medium=articlePDFlink%26utm_source=articlePDF%26utm_content=jamainternmed.2022.6555

Bao, Bertoia, Lenart, Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses' Health Studies, Am J Public Health, doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303338

Beavers, Brinkley, Nicklas, Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation, Clin Chim Acta, doi:10.1016/j.cca.2010.02.069

Behan, Behan, Gow, Cavanagh, Gillespie, Enteroviruses and postviral fatigue syndrome, Ciba Found Symp, doi:10.1002/9780470514382.ch9

Bouton, Why behavior change is difficult to sustain, Prev Med, doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.010

Childs, Calder, Miles, Diet and immune function, Nutrients, doi:10.3390/nu11081933

Chiuve, Fung, Rimm, Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire, Int J Epidemiol, doi:10.1093/sleep/27.3.440

Chiva-Blanch, Badimon, Benefits and risks of moderate alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease: current findings and controversies, Nutrients, doi:10.3390/nu12010108

Choutka, Jansari, Hornig, Iwasaki, Author correction: unexplained post-acute infection syndromes, Nat Med, doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01952-7

Cobre, Surek, Vilhena, Influence of foods and nutrients on COVID-19 recovery: a multivariate analysis of data from 170 countries using a generalized linear model, Clin Nutr, doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.018

Corrao, Bagnardi, Zambon, Vecchia, A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases, Prev Med, doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027

Costenbader, Karlson, Cigarette smoking and autoimmune disease: what can we learn from epidemiology?, Lupus, doi:10.1177/0961203306069344

Crook, Raza, Nowell, Young, Long COVID-mechanisms, risk factors, and management, BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.n1648

Evans, Mcauley, Harrison, Physical, cognitive, and mental health impacts of COVID-19 after hospitalisation (PHOSP-COVID): a UK multicentre, prospective cohort study, Lancet Respir Med, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00383-0

For, Control, Nearly one in five american adults who have had COVID-19 still have "long COVID

Go, COVID-19 for health professionals: post COVID-19 condition

Goldhaber, Fanikos, Stämpfli, Anderson, How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer, Nat Rev Immunol, doi:10.1038/nri2530

Hamer, Kivimäki, Gale, Batty, Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK, Brain Behav Immun, doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.059

Huang, Goodman, Li, COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management, Nat Rev Endocrinol, doi:10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4

Huang, Tobias, Hruby, Rifai, Tworoger et al., An increase in dietary quality is associated with favorable plasma biomarkers of the brain-adipose axis in apparently healthy US women, J Nutr, doi:10.3945/jn.115.229666

Ibarra-Coronado, Pantaleón-Martínez, Velazquéz-Moctezuma, The bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity against infections, J Immunol Res, doi:10.1155/2015/678164

Imhof, Froehlich, Brenner, Boeing, Pepys et al., Effect of alcohol consumption on systemic markers of inflammation, Lancet, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04170-2

Iqbal, Lam, Sounderajah, Clarke, Ashrafian et al., Characteristics and predictors of acute and chronic post-COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis, EClinicalMedicine, doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100899

Khunti, Davies, Kosiborod, Nauck, Long COVID-metabolic risk factors and novel therapeutic management, Nat Rev Endocrinol, doi:10.1038/s41574-021-00495-0

Korakas, Ikonomidis, Kousathana, Obesity and COVID-19: immune and metabolic derangement as a possible link to adverse clinical outcomes, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00198.2020

Lee, Chakladar, Li, Tobacco, but not nicotine and flavor-less electronic cigarettes, induces ACE2 and immune dysregulation, Int J Mol Sci, doi:10.3390/ijms21155513

Lee, Taneja, Vassallo, Cigarette smoking and inflammation: cellular and molecular mechanisms, J Dent Res, doi:10.1177/0022034511421200

Li, Pan, Wang, Impact of healthy lifestyle factors on life expectancies in the US population, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032047

Lu, Solomon, Costenbader, Keenan, Chibnik et al., Alcohol consumption and markers of inflammation in women with preclinical rheumatoid arthritis, Arthritis Rheum, doi:10.1002/art.27739

Manzel, Muller, Hafler, Erdman, Linker et al., Role of "Western diet" in inflammatory autoimmune diseases, Curr Allergy Asthma Rep, doi:10.1007/s11882-013-0404-6

Mehandru, Merad, Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID, Nat Immunol, doi:10.1038/s41590-021-01104-y

Milner, Beck, The impact of obesity on the immune response to infection, Proc Nutr Soc, doi:10.1017/S0029665112000158

Molina, Happel, Zhang, Kolls, Nelson, Focus on: alcohol and the immune system, Alcohol Res Health

Monteiro, Azevedo, Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome, Mediators Inflamm, doi:10.1155/2010/289645

Mullington, Simpson, Meier-Ewert, Haack, Sleep loss and inflammation, Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab, doi:10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.014

Munblit, Hara, Akrami, Perego, Olliaro et al., Long COVID: aiming for a consensus, Lancet Respir Med, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00135-7

Nalbandian, Sehgal, Gupta, Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, Nat Med, doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

Pinto, Roschel, De, Pinto, Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior: overlooked risk factors in autoimmune rheumatic diseases?, Autoimmun Rev, doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.05.001

Pischon, Hankinson, Hotamisligil, Rifai, Rimm, Leisure-time physical activity and reduced plasma levels of obesity-related inflammatory markers, Obes Res, doi:10.1038/oby.2003.145

Prasannan, Heightman, Hillman, Impaired exercise capacity in post-COVID-19 syndrome: the role of VWF-ADAMTS13 axis, Blood Adv, doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006944

Rothman, Greenland, Lash, Modern Epidemiology

Subramanian, Nirantharakumar, Hughes, Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults, Nat Med, doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w

Sudre, Murray, Varsavsky, Attributes and predictors of long COVID, Nat Med, doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y

Tenforde, Kim, Lindsell, Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network-United States, March, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1

Thompson, Williams, Walker, Long COVID burden and risk factors in 10 UK longitudinal studies and electronic health records, Nat Commun, doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30836-0

Troy, Hunter, Manson, Colditz, Stampfer et al., The validity of recalled weight among younger women, Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord

Versini, Jeandel, Rosenthal, Shoenfeld, Zielinski et al., Obesity in autoimmune diseases: not a passive bystander, Autoimmun Rev, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01827

Wang, Quan, Chavarro, Associations of depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, and loneliness prior to infection with risk of post-COVID-19 conditions, JAMA Psychiatry, doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2640?utm_campaign=articlePDF%26utm_medium=articlePDFlink%26utm_source=articlePDF%26utm_content=jamainternmed.2022.6555

Watson, Badr, Belenky, Consensus Conference Panel. Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion, Sleep, doi:10.5665/sleep.4886

Woods, Ceddia, Wolters, Evans, Lu et al., Effects of 6 months of moderate aerobic exercise training on immune function in the elderly, Mech Ageing Dev, doi:10.1016/S0047-6374(99)00014-7

Yu, Rohli, Yang, Jia, Impact of obesity on COVID-19 patients, J Diabetes Complications, doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107817

Yuan, Spiegelman, Rimm, Relative validity of nutrient intakes assessed by questionnaire, 24-hour recalls, and diet records as compared with urinary recovery and plasma concentration biomarkers: findings for women, Am J Epidemiol, doi:10.1093/aje/kwx328

Yuan, Spiegelman, Rimm, Validity of a dietary questionnaire assessed by comparison with multiple weighed dietary records or 24-hour recalls, Am J Epidemiol, doi:10.1093/aje/kww104

Zhang, Xu, Xie, Poor-sleep is associated with slow recovery from lymphopenia and an increased need for ICU care in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study, Brain Behav Immun, doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.075

DOI record:

{

"DOI": "10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6555",

"ISSN": [

"2168-6106"

],

"URL": "http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6555",

"abstract": "<jats:sec id=\"ab-ioi220085-4\"><jats:title>Importance</jats:title><jats:p>Few modifiable risk factors for post–COVID-19 condition (PCC) have been identified.</jats:p></jats:sec><jats:sec id=\"ab-ioi220085-5\"><jats:title>Objective</jats:title><jats:p>To investigate the association between healthy lifestyle factors prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of PCC.</jats:p></jats:sec><jats:sec id=\"ab-ioi220085-6\"><jats:title>Design, Setting, and Participants</jats:title><jats:p>In this prospective cohort study, 32 249 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort reported preinfection lifestyle habits in 2015 and 2017. Healthy lifestyle factors included healthy body mass index (BMI, 18.5-24.9; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), never smoking, at least 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity, moderate alcohol intake (5 to 15 g/d), high diet quality (upper 40% of Alternate Healthy Eating Index–2010 score), and adequate sleep (7 to 9 h/d).</jats:p></jats:sec><jats:sec id=\"ab-ioi220085-7\"><jats:title>Main Outcomes and Measures</jats:title><jats:p>SARS-CoV-2 infection (confirmed by test) and PCC (at least 4 weeks of symptoms) were self-reported on 7 periodic surveys administered from April 2020 to November 2021. Among participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the relative risk (RR) of PCC in association with the number of healthy lifestyle factors (0 to 6) was estimated using Poisson regression and adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities.</jats:p></jats:sec><jats:sec id=\"ab-ioi220085-8\"><jats:title>Results</jats:title><jats:p>A total of 1981 women with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test over 19 months of follow-up were documented. Among those participants, mean age was 64.7 years (SD, 4.6; range, 55-75); 97.4% (n = 1929) were White; and 42.8% (n = 848) were active health care workers. Among these, 871 (44.0%) developed PCC. Healthy lifestyle was associated with lower risk of PCC in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with women without any healthy lifestyle factors, those with 5 to 6 had 49% lower risk (RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.33-0.78) of PCC. In a model mutually adjusted for all lifestyle factors, BMI and sleep were independently associated with risk of PCC (BMI, 18.5-24.9 vs others, RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-1.00, <jats:italic>P</jats:italic> = .046; sleep, 7-9 h/d vs others, RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.95, <jats:italic>P</jats:italic> = .008). If these associations were causal, 36.0% of PCC cases would have been prevented if all participants had 5 to 6 healthy lifestyle factors (population attributable risk percentage, 36.0%; 95% CI, 14.1%-52.7%). Results were comparable when PCC was defined as symptoms of at least 2-month duration or having ongoing symptoms at the time of PCC assessment.</jats:p></jats:sec><jats:sec id=\"ab-ioi220085-9\"><jats:title>Conclusions and Relevance</jats:title><jats:p>In this prospective cohort study, pre-infection healthy lifestyle was associated with a substantially lower risk of PCC. Future research should investigate whether lifestyle interventions may reduce risk of developing PCC or mitigate symptoms among individuals with PCC or possibly other postinfection syndromes.</jats:p></jats:sec>",

"author": [

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Wang",

"given": "Siwen",

"sequence": "first"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Li",

"given": "Yanping",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Yue",

"given": "Yiyang",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

},

{

"name": "Zhejiang University School of Public Health, Hangzhou, China"

}

],

"family": "Yuan",

"given": "Changzheng",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Kang",

"given": "Jae Hee",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

},

{

"name": "Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts"

},

{

"name": "Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Chavarro",

"given": "Jorge E.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

},

{

"name": "Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Bhupathiraju",

"given": "Shilpa N.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Department of Environmental Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts"

}

],

"family": "Roberts",

"given": "Andrea L.",

"sequence": "additional"

}

],

"container-title": "JAMA Internal Medicine",

"container-title-short": "JAMA Intern Med",

"content-domain": {

"crossmark-restriction": false,

"domain": []

},

"created": {

"date-parts": [

[

2023,

2,

6

]

],

"date-time": "2023-02-06T16:06:28Z",

"timestamp": 1675699588000

},

"deposited": {

"date-parts": [

[

2023,

2,

6

]

],

"date-time": "2023-02-06T16:06:42Z",

"timestamp": 1675699602000

},

"indexed": {

"date-parts": [

[

2023,

2,

7

]

],

"date-time": "2023-02-07T05:32:29Z",

"timestamp": 1675747949138

},

"is-referenced-by-count": 0,

"issued": {

"date-parts": [

[

2023,

2,

6

]

]

},

"language": "en",

"link": [

{

"URL": "https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/articlepdf/2800885/jamainternal_wang_2023_oi_220085_1674248303.53655.pdf",

"content-type": "unspecified",

"content-version": "vor",

"intended-application": "similarity-checking"

}

],

"member": "10",

"original-title": [],

"prefix": "10.1001",

"published": {

"date-parts": [

[

2023,

2,

6

]

]

},

"published-online": {

"date-parts": [

[

2023,

2,

6

]

]

},

"publisher": "American Medical Association (AMA)",

"reference": [

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100899",

"article-title": "Characteristics and predictors of acute and chronic post-COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis.",

"author": "Iqbal",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"journal-title": "EClinicalMedicine",

"key": "ioi220085r4",

"volume": "36",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00383-0",

"article-title": "Physical, cognitive, and mental health impacts of COVID-19 after hospitalisation (PHOSP-COVID): a UK multicentre, prospective cohort study.",

"author": "Evans",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1275",

"issue": "11",

"journal-title": "Lancet Respir Med",

"key": "ioi220085r5",

"volume": "9",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1001/jama.2022.11691",

"article-title": "Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and long COVID after infections not requiring hospitalization in health care workers.",

"author": "Azzolini",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "676",

"issue": "7",

"journal-title": "JAMA",

"key": "ioi220085r6",

"volume": "328",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z",

"article-title": "Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome.",

"author": "Nalbandian",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "601",

"issue": "4",

"journal-title": "Nat Med",

"key": "ioi220085r7",

"volume": "27",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1136/bmj.n1648",

"article-title": "Long COVID—mechanisms, risk factors, and management.",

"author": "Crook",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "n1648",

"issue": "1648",

"journal-title": "BMJ",

"key": "ioi220085r9",

"volume": "374",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41590-021-01104-y",

"article-title": "Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID.",

"author": "Mehandru",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "194",

"issue": "2",

"journal-title": "Nat Immunol",

"key": "ioi220085r10",

"volume": "23",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41591-022-01952-7",

"article-title": "Author correction: unexplained post-acute infection syndromes.",

"author": "Choutka",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1723",

"issue": "8",

"journal-title": "Nat Med",

"key": "ioi220085r11",

"volume": "28",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1002/9780470514382.ch9",

"article-title": "Enteroviruses and postviral fatigue syndrome.",

"author": "Behan",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "146",

"journal-title": "Ciba Found Symp",

"key": "ioi220085r12",

"volume": "173",

"year": "1993"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1155/2010/289645",

"article-title": "Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome.",

"author": "Monteiro",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"journal-title": "Mediators Inflamm",

"key": "ioi220085r13",

"volume": "2010",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1177/0022034511421200",

"article-title": "Cigarette smoking and inflammation: cellular and molecular mechanisms.",

"author": "Lee",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "142",

"issue": "2",

"journal-title": "J Dent Res",

"key": "ioi220085r14",

"volume": "91",

"year": "2012"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.10.002",

"article-title": "Long-term adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and chronic inflammation in the prospective Whitehall II study.",

"author": "Akbaraly",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "152",

"issue": "2",

"journal-title": "Am J Med",

"key": "ioi220085r15",

"volume": "128",

"year": "2015"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04170-2",

"article-title": "Effect of alcohol consumption on systemic markers of inflammation.",

"author": "Imhof",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "763",

"issue": "9258",

"journal-title": "Lancet",

"key": "ioi220085r16",

"volume": "357",

"year": "2001"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.cca.2010.02.069",

"article-title": "Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation.",

"author": "Beavers",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "785",

"issue": "11-12",

"journal-title": "Clin Chim Acta",

"key": "ioi220085r17",

"volume": "411",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.014",

"article-title": "Sleep loss and inflammation.",

"author": "Mullington",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "775",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab",

"key": "ioi220085r18",

"volume": "24",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.022",

"article-title": "Lifestyle risk factors and infectious disease mortality, including COVID-19, among middle aged and older adults: evidence from a community-based cohort study in the United Kingdom.",

"author": "Ahmadi",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "18",

"journal-title": "Brain Behav Immun",

"key": "ioi220085r19",

"volume": "96",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.059",

"article-title": "Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK.",

"author": "Hamer",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "184",

"journal-title": "Brain Behav Immun",

"key": "ioi220085r20",

"volume": "87",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w",

"article-title": "Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults.",

"author": "Subramanian",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1706",

"issue": "8",

"journal-title": "Nat Med",

"key": "ioi220085r21",

"volume": "28",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1",

"article-title": "Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network—United States, March-June 2020.",

"author": "Tenforde",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "993",

"issue": "30",

"journal-title": "MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep",

"key": "ioi220085r22",

"volume": "69",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41467-022-30836-0",

"article-title": "Long COVID burden and risk factors in 10 UK longitudinal studies and electronic health records.",

"author": "Thompson",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "3528",

"issue": "1",

"journal-title": "Nat Commun",

"key": "ioi220085r23",

"volume": "13",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y",

"article-title": "Attributes and predictors of long COVID.",

"author": "Sudre",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "626",

"issue": "4",

"journal-title": "Nat Med",

"key": "ioi220085r24",

"volume": "27",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.2105/AJPH.2016.303338",

"article-title": "Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses’ Health Studies.",

"author": "Bao",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1573",

"issue": "9",

"journal-title": "Am J Public Health",

"key": "ioi220085r25",

"volume": "106",

"year": "2016"

},

{

"article-title": "The validity of recalled weight among younger women.",

"author": "Troy",

"first-page": "570",

"issue": "8",

"journal-title": "Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord",

"key": "ioi220085r26",

"volume": "19",

"year": "1995"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2695",

"article-title": "Measurement of tobacco smoke exposure: comparison of toenail nicotine biomarkers and self-reports.",

"author": "Al-Delaimy",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1255",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev",

"key": "ioi220085r27",

"volume": "17",

"year": "2008"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/aje/kww104",

"article-title": "Validity of a dietary questionnaire assessed by comparison with multiple weighed dietary records or 24-hour recalls.",

"author": "Yuan",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "570",

"issue": "7",

"journal-title": "Am J Epidemiol",

"key": "ioi220085r28",

"volume": "185",

"year": "2017"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/aje/kwx328",

"article-title": "Relative validity of nutrient intakes assessed by questionnaire, 24-hour recalls, and diet records as compared with urinary recovery and plasma concentration biomarkers: findings for women.",

"author": "Yuan",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1051",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Am J Epidemiol",

"key": "ioi220085r29",

"volume": "187",

"year": "2018"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3945/jn.111.157222",

"article-title": "Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease.",

"author": "Chiuve",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1009",

"issue": "6",

"journal-title": "J Nutr",

"key": "ioi220085r30",

"volume": "142",

"year": "2012"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/ije/23.5.991",

"article-title": "Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire.",

"author": "Wolf",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "991",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Int J Epidemiol",

"key": "ioi220085r31",

"volume": "23",

"year": "1994"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/sleep/27.3.440",

"article-title": "A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women.",

"author": "Patel",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "440",

"issue": "3",

"journal-title": "Sleep",

"key": "ioi220085r32",

"volume": "27",

"year": "2004"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032047",

"article-title": "Impact of healthy lifestyle factors on life expectancies in the US population.",

"author": "Li",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "345",

"issue": "4",

"journal-title": "Circulation",

"key": "ioi220085r33",

"volume": "138",

"year": "2018"

},

{

"DOI": "10.5665/sleep.4886",

"article-title": "Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion.",

"author": "Watson",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1161",

"issue": "8",

"journal-title": "Sleep",

"key": "ioi220085r36",

"volume": "38",

"year": "2015"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2640",

"article-title": "Associations of depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, and loneliness prior to infection with risk of post-COVID-19 conditions.",

"author": "Wang",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1081",

"issue": "11",

"journal-title": "JAMA Psychiatry",

"key": "ioi220085r37",

"volume": "79",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3390/nu12010108",

"article-title": "Benefits and risks of moderate alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease: current findings and controversies.",

"author": "Chiva-Blanch",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "108",

"issue": "1",

"journal-title": "Nutrients",

"key": "ioi220085r39",

"volume": "12",

"year": "2019"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027",

"article-title": "A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases.",

"author": "Corrao",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "613",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Prev Med",

"key": "ioi220085r40",

"volume": "38",

"year": "2004"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.018",

"article-title": "Influence of foods and nutrients on COVID-19 recovery: a multivariate analysis of data from 170 countries using a generalized linear model.",

"author": "Cobre",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "3077",

"issue": "12",

"journal-title": "Clin Nutr",

"key": "ioi220085r41",

"volume": "41",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107817",

"article-title": "Impact of obesity on COVID-19 patients.",

"author": "Yu",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"issue": "3",

"journal-title": "J Diabetes Complications",

"key": "ioi220085r42",

"volume": "35",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.075",

"article-title": "Poor-sleep is associated with slow recovery from lymphopenia and an increased need for ICU care in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study.",

"author": "Zhang",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "50",

"journal-title": "Brain Behav Immun",

"key": "ioi220085r43",

"volume": "88",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S0047-6374(99)00014-7",

"article-title": "Effects of 6 months of moderate aerobic exercise training on immune function in the elderly.",

"author": "Woods",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1",

"issue": "1",

"journal-title": "Mech Ageing Dev",

"key": "ioi220085r44",

"volume": "109",

"year": "1999"

},

{

"article-title": "Focus on: alcohol and the immune system.",

"author": "Molina",

"first-page": "97",

"issue": "1-2",

"journal-title": "Alcohol Res Health",

"key": "ioi220085r45",

"volume": "33",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1152/ajpendo.00198.2020",

"article-title": "Obesity and COVID-19: immune and metabolic derangement as a possible link to adverse clinical outcomes.",

"author": "Korakas",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "E105",

"issue": "1",

"journal-title": "Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab",

"key": "ioi220085r46",

"volume": "319",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3390/ijms21155513",

"article-title": "Tobacco, but not nicotine and flavor-less electronic cigarettes, induces ACE2 and immune dysregulation.",

"author": "Lee",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "5513",

"issue": "15",

"journal-title": "Int J Mol Sci",

"key": "ioi220085r47",

"volume": "21",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.2174/1874306401105010031",

"article-title": "Metabolic, endocrine, and immune consequences of sleep deprivation.",

"author": "Aldabal",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "31",

"journal-title": "Open Respir Med J",

"key": "ioi220085r48",

"volume": "5",

"year": "2011"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3390/nu11081933",

"article-title": "Diet and immune function.",

"author": "Childs",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1933",

"issue": "8",

"journal-title": "Nutrients",

"key": "ioi220085r49",

"volume": "11",

"year": "2019"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/oby.2003.145",

"article-title": "Leisure-time physical activity and reduced plasma levels of obesity-related inflammatory markers.",

"author": "Pischon",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1055",

"issue": "9",

"journal-title": "Obes Res",

"key": "ioi220085r50",

"volume": "11",

"year": "2003"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1002/art.27739",

"article-title": "Alcohol consumption and markers of inflammation in women with preclinical rheumatoid arthritis.",

"author": "Lu",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "3554",

"issue": "12",

"journal-title": "Arthritis Rheum",

"key": "ioi220085r51",

"volume": "62",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3945/jn.115.229666",

"article-title": "An increase in dietary quality is associated with favorable plasma biomarkers of the brain-adipose axis in apparently healthy US women.",

"author": "Huang",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1101",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "J Nutr",

"key": "ioi220085r52",

"volume": "146",

"year": "2016"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.060",

"article-title": "C-reactive protein and risk of OSA in four US cohorts.",

"author": "Huang",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "2439",

"issue": "6",

"journal-title": "Chest",

"key": "ioi220085r53",

"volume": "159",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4",

"article-title": "COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management.",

"author": "Lim",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "11",

"issue": "1",

"journal-title": "Nat Rev Endocrinol",

"key": "ioi220085r54",

"volume": "17",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/s41574-021-00495-0",

"article-title": "Long COVID—metabolic risk factors and novel therapeutic management.",

"author": "Khunti",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "379",

"issue": "7",

"journal-title": "Nat Rev Endocrinol",

"key": "ioi220085r55",

"volume": "17",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.autrev.2014.07.001",

"article-title": "Obesity in autoimmune diseases: not a passive bystander.",

"author": "Versini",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "981",

"issue": "9",

"journal-title": "Autoimmun Rev",

"key": "ioi220085r56",

"volume": "13",

"year": "2014"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3389/fimmu.2019.01827",

"article-title": "Fatigue, sleep, and autoimmune and related disorders.",

"author": "Zielinski",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "1827",

"journal-title": "Front Immunol",

"key": "ioi220085r57",

"volume": "10",

"year": "2019"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1177/0961203306069344",

"article-title": "Cigarette smoking and autoimmune disease: what can we learn from epidemiology?",

"author": "Costenbader",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "737",

"issue": "11",

"journal-title": "Lupus",

"key": "ioi220085r58",

"volume": "15",

"year": "2006"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1007/s11882-013-0404-6",

"article-title": "Role of “Western diet” in inflammatory autoimmune diseases.",

"author": "Manzel",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "404",

"issue": "1",

"journal-title": "Curr Allergy Asthma Rep",

"key": "ioi220085r59",

"volume": "14",

"year": "2014"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.autrev.2017.05.001",

"article-title": "Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior: overlooked risk factors in autoimmune rheumatic diseases?",

"author": "Pinto",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "667",

"issue": "7",

"journal-title": "Autoimmun Rev",

"key": "ioi220085r60",

"volume": "16",

"year": "2017"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006944",

"article-title": "Impaired exercise capacity in post-COVID-19 syndrome: the role of VWF-ADAMTS13 axis.",

"author": "Prasannan",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "4041",

"issue": "13",

"journal-title": "Blood Adv",

"key": "ioi220085r61",

"volume": "6",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1161/01.CIR.0000145141.70264.C5",

"article-title": "Cardiology patient pages: prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.",

"author": "Goldhaber",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "e445",

"issue": "16",

"journal-title": "Circulation",

"key": "ioi220085r62",

"volume": "110",

"year": "2004"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1038/nri2530",

"article-title": "How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer.",

"author": "Stämpfli",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "377",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Nat Rev Immunol",

"key": "ioi220085r63",

"volume": "9",

"year": "2009"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1155/2015/678164",

"article-title": "The bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity against infections.",

"author": "Ibarra-Coronado",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"journal-title": "J Immunol Res",

"key": "ioi220085r64",

"volume": "2015",

"year": "2015"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1017/S0029665112000158",

"article-title": "The impact of obesity on the immune response to infection.",

"author": "Milner",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "298",

"issue": "2",

"journal-title": "Proc Nutr Soc",

"key": "ioi220085r65",

"volume": "71",

"year": "2012"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00941-2",

"article-title": "Risk of long COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2.",

"author": "Antonelli",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "2263",

"issue": "10343",

"journal-title": "Lancet",

"key": "ioi220085r66",

"volume": "399",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00135-7",

"article-title": "Long COVID: aiming for a consensus.",

"author": "Munblit",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "632",

"issue": "7",

"journal-title": "Lancet Respir Med",

"key": "ioi220085r67",

"volume": "10",

"year": "2022"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.010",

"article-title": "Why behavior change is difficult to sustain.",

"author": "Bouton",

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"first-page": "29",

"journal-title": "Prev Med",

"key": "ioi220085r68",

"volume": "68",

"year": "2014"

},

{

"author": "Rothman",

"key": "ioi220085r38",

"volume-title": "Modern Epidemiology",

"year": "2008"

},

{

"key": "ioi220085r1",

"unstructured": "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated December 16, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html"

},

{

"key": "ioi220085r2",

"unstructured": "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly one in five american adults who have had COVID-19 still have “long COVID.” June 22, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/20220622.htm"

},

{

"key": "ioi220085r3",

"unstructured": "Canada Go. COVID-19 for health professionals: post COVID-19 condition (long COVID). Updated October 20, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/post-covid-19-condition.html"

},

{

"key": "ioi220085r8",

"unstructured": "U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Biden–Harris administration releases two new reports on long COVID to support patients and further research. August 3, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/08/03/biden-harris-administration-releases-two-new-reports-long-covid-support-patients-further-research.html"

},

{

"key": "ioi220085r34",

"unstructured": "World Health Organization. Body mass index (BMI). Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/body-mass-index?introPage=intro_3.html"

},

{

"key": "ioi220085r35",

"unstructured": "U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/physical-activity-guidelines/current-guidelines/scientific-report"

}

],

"reference-count": 68,

"references-count": 68,

"relation": {},

"resource": {

"primary": {

"URL": "https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2800885"

}

},

"score": 1,

"short-title": [],

"source": "Crossref",

"subject": [

"Internal Medicine"

],

"subtitle": [],

"title": "Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Prior to Infection and Risk of Post–COVID-19 Condition",

"type": "journal-article"

}

wang10