Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank

et al., Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews, 14:4, 561–565, doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050, Aug 2020

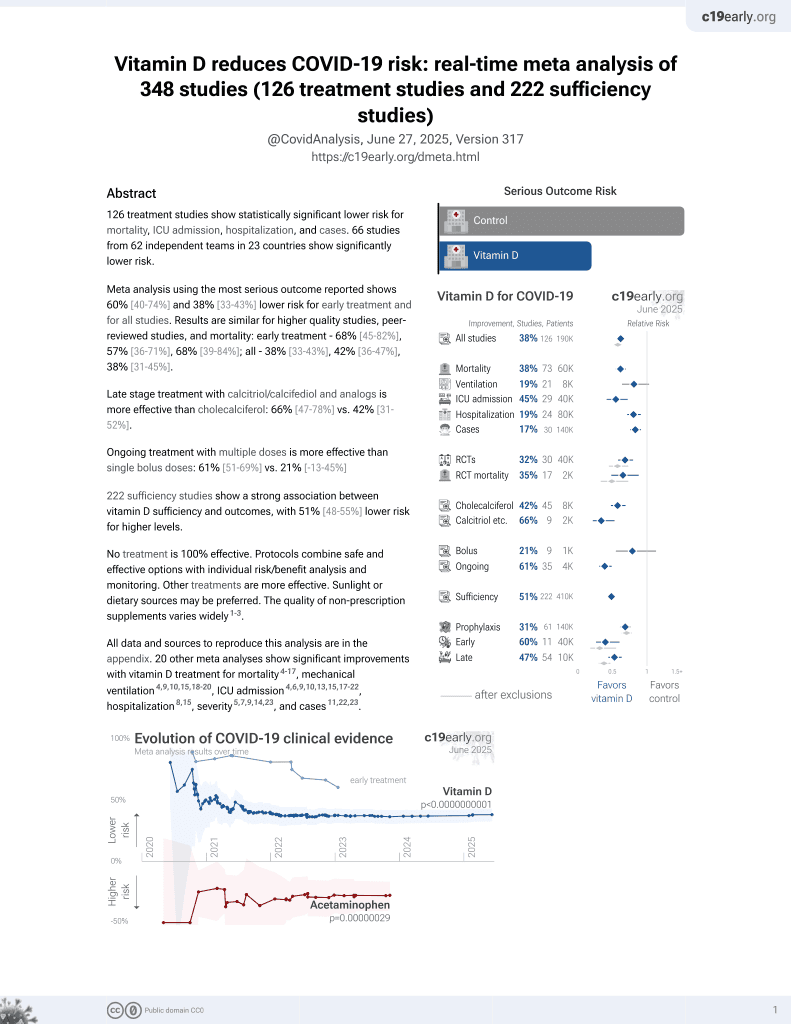

Vitamin D for COVID-19

8th treatment shown to reduce risk in

October 2020, now with p < 0.00000000001 from 135 studies, recognized in 18 countries.

No treatment is 100% effective. Protocols

combine treatments.

6,400+ studies for

210+ treatments. c19early.org

|

Database analysis of 341,484 patients in the UK with 656 hospitalized confirmed COVID-19 patients and 203 deaths, not showing a statistically significant difference after adjustment. Since adjustment factors may be correlated with vitamin D deficiency, the extent of any causal contribution of both vitamin D and the adjustment factors is unclear.

There was an ~10 year time period between baseline 25(OH)D measurement and COVID-19 infection, with 84% concordance for a subsample with measurements ~4.3 years later. Vitamin D levels may change significantly across seasons and years. People that discovered they had low vitamin D levels may have been encouraged to take steps to correct the deficiency.

Davies et al. raise a number of concerns with this study1, reporting that it lacked power, suffered low precision and high bias, used flawed models, and contained many serious statistical errors. 1. Mislabelled data artificially inflated the control set, creating an illusion of high power & precision in an underpowered data set study, 2. Logistic regression violated multiple prerequisite conditions, creating biased results and a further reduction of power (overfit, over-adjusted, poor variable types, and poor handling), and 3. Unreliable data in the logistic regressions caused regression dilution bias, bias amplification, and further loss of power and precision.

See also2.

This is the 11th of 228 COVID-19 sufficiency studies for vitamin D, which collectively show higher levels reduce risk with p<0.0000000001.

Standard of Care (SOC) for COVID-19 in the study country,

the United Kingdom, is very poor with very low average efficacy for approved treatments3.

The United Kingdom focused on expensive high-profit treatments, approving only one low-cost early treatment, which required a prescription and had limited adoption. The high-cost prescription treatment strategy reduces the probability of early treatment due to access and cost barriers, and eliminates complementary and synergistic benefits seen with many low-cost treatments.

|

risk of death, 17.4% lower, RR 0.83, p = 0.31, cutoff 25nmol/L, adjusted per study, inverted to make RR<1 favor high D levels (≥25nmol/L), multivariable Cox.

|

|

risk of hospitalization, 9.1% lower, RR 0.91, p = 0.40, cutoff 25nmol/L, adjusted per study, inverted to make RR<1 favor high D levels (≥25nmol/L), multivariable Cox.

|

| Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules prioritizing more serious outcomes. Submit updates |

Hastie et al., 26 Aug 2020, retrospective, population-based cohort, database analysis, United Kingdom, peer-reviewed, 14 authors.

Vitamin D and COVID-19 infection and mortality in UK Biobank

European Journal of Nutrition, doi:10.1007/s00394-020-02372-4

Purpose Low blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration has been proposed as a potential causal factor in COVID-19 risk. We aimed to establish whether baseline serum 25(OH)D concentration was associated with COVID-19 mortality, and inpatient confirmed COVID-19 infection, in UK Biobank participants. Methods UK Biobank recruited 502,624 participants aged 37-73 years between 2006 and 2010. Baseline exposure data, including serum 25(OH)D concentration, were linked to COVID-19 mortality. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed for the association between 25(OH)D and COVID-19 death, and Poisson regression analyses for the association between 25(OH)D and severe COVID-19 infection. Results Complete data were available for 341,484 UK Biobank participants, of which 656 had inpatient confirmed COVID-19 infection and 203 died of COVID-19 infection. 25(OH)D concentration was associated with severe COVID-19 infection and mortality univariably (mortality per 10 nmol/L 25(OH)D HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.86-0.98; p = 0.016), but not after adjustment for confounders (mortality per 10 nmol/L 25(OH)D HR 0.98; 95% CI = 0.91-1.06; p = 0.696). Vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency was also not independently associated with either COVID-19 infection or linked mortality. Conclusions Our findings do not support a potential link between 25(OH)D concentrations and risk of severe COVID-19 infection and mortality. Randomised trials are needed to prove a beneficial role for vitamin D in the prevention of severe COVID-19 reactions or death.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Ethics approval UK Biobank received ethical approval from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 16/ NW/0274) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent All participants gave written informed consent for data collection, analysis, and record linkage. All participants gave written informed consent for publication of research. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creat iveco mmons .org/licen ses/by/4.0/.

References

Hastie, Mackay, Ho, Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank, Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev, doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050

Mitchell, Vitamin-D and COVID-19: do deficient risk a poorer outcome?, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30183-2

Nhs, Vitamins and minerals: Vitamin D

Nice, COVID-19 rapid evidence summary:vitamin D for COVID-19

Raisi-Estabragh, Mccracken, Bethell, Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25(OH)-vitamin D status: study of 1326 cases from the UK Biobank, doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdaa095

Sattar, Welsh, Panarelli, Forouhi, Increasing requests for vitamin D measurement: costly, confusing, and without credibility, Lancet, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61816-3

DOI record:

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050",

"ISSN": [

"1871-4021"

],

"URL": "http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050",

"alternative-id": [

"S1871402120301156"

],

"assertion": [

{

"label": "This article is maintained by",

"name": "publisher",

"value": "Elsevier"

},

{

"label": "Article Title",

"name": "articletitle",

"value": "Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank"

},

{

"label": "Journal Title",

"name": "journaltitle",

"value": "Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews"

},

{

"label": "CrossRef DOI link to publisher maintained version",

"name": "articlelink",

"value": "https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050"

},

{

"label": "Content Type",

"name": "content_type",

"value": "article"

},

{

"label": "Copyright",

"name": "copyright",

"value": "© 2020 Diabetes India. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved."

}

],

"author": [

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4604-3319",

"affiliation": [],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Hastie",

"given": "Claire E.",

"sequence": "first"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Mackay",

"given": "Daniel F.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7190-9025",

"affiliation": [],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Ho",

"given": "Frederick",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Celis-Morales",

"given": "Carlos A.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6593-9092",

"affiliation": [],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Katikireddi",

"given": "Srinivasa Vittal",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Niedzwiedz",

"given": "Claire L.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Jani",

"given": "Bhautesh D.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Welsh",

"given": "Paul",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9780-1135",

"affiliation": [],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Mair",

"given": "Frances S.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Gray",

"given": "Stuart R.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5368-3779",

"affiliation": [],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "O’Donnell",

"given": "Catherine A.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3615-0986",

"affiliation": [],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Gill",

"given": "Jason MR.",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Sattar",

"given": "Naveed",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [],

"family": "Pell",

"given": "Jill P.",

"sequence": "additional"

}

],

"container-title": "Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews",

"container-title-short": "Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews",

"content-domain": {

"crossmark-restriction": true,

"domain": [

"clinicalkey.jp",

"clinicalkey.com",

"clinicalkey.es",

"clinicalkey.fr",

"clinicalkey.com.au",

"elsevier.com",

"sciencedirect.com"

]

},

"created": {

"date-parts": [

[

2020,

5,

7

]

],

"date-time": "2020-05-07T16:04:07Z",

"timestamp": 1588867447000

},

"deposited": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

9,

28

]

],

"date-time": "2021-09-28T10:12:29Z",

"timestamp": 1632823949000

},

"funder": [

{

"name": "Health Data Research-UK"

},

{

"award": [

"SCAF/15/02"

],

"name": "NRS Senior Clinical Fellowship"

},

{

"DOI": "10.13039/501100000265",

"award": [

"MC_UU_12017/13"

],

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"name": "Medical Research Council"

},

{

"DOI": "10.13039/501100000589",

"award": [

"SPHSU13"

],

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"name": "Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office"

},

{

"DOI": "10.13039/501100000265",

"award": [

"MR/R024774/1"

],

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"name": "Medical Research Council"

},

{

"DOI": "10.13039/501100000274",

"award": [

"RE/18/6/34217"

],

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"name": "British Heart Foundation Research Excellence Award"

}

],

"indexed": {

"date-parts": [

[

2024,

4,

8

]

],

"date-time": "2024-04-08T09:11:34Z",

"timestamp": 1712567494519

},

"is-referenced-by-count": 342,

"issue": "4",

"issued": {

"date-parts": [

[

2020,

7

]

]

},

"journal-issue": {

"issue": "4",

"published-print": {

"date-parts": [

[

2020,

7

]

]

}

},

"language": "en",

"license": [

{

"URL": "https://www.elsevier.com/tdm/userlicense/1.0/",

"content-version": "tdm",

"delay-in-days": 0,

"start": {

"date-parts": [

[

2020,

7,

1

]

],

"date-time": "2020-07-01T00:00:00Z",

"timestamp": 1593561600000

}

}

],

"link": [

{

"URL": "https://api.elsevier.com/content/article/PII:S1871402120301156?httpAccept=text/xml",

"content-type": "text/xml",

"content-version": "vor",

"intended-application": "text-mining"

},

{

"URL": "https://api.elsevier.com/content/article/PII:S1871402120301156?httpAccept=text/plain",

"content-type": "text/plain",

"content-version": "vor",

"intended-application": "text-mining"

}

],

"member": "78",

"original-title": [],

"page": "561-565",

"prefix": "10.1016",

"published": {

"date-parts": [

[

2020,

7

]

]

},

"published-print": {

"date-parts": [

[

2020,

7

]

]

},

"publisher": "Elsevier BV",

"reference": [

{

"author": "Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib1",

"series-title": "Covid-19 study case mix programme",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"author": "Office for National Statistics",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib2"

},

{

"author": "John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib3"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1136/bmj.m1548",

"article-title": "Is ethnicity linked to incidence or outcomes of covid-19?",

"author": "Khunti",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "m1548",

"journal-title": "BMJ",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib4",

"volume": "369",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"author": "UK Government",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib5"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2006.01.003",

"article-title": "CVD risk factors and ethnicity–a homogeneous relationship?",

"author": "Forouhi",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "11",

"journal-title": "Atherosclerosis Suppl",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib6",

"volume": "7",

"year": "2006"

},

{

"article-title": "Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4,103 patients with COVID-19 disease in New York City",

"author": "Petrilli",

"journal-title": "medRxiv",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib7",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"article-title": "The epidemiological and clinical features of COVID-19 and lessons from this global infectious public health event",

"author": "Tu",

"journal-title": "J Infect",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib8",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1136/bmj.g2035",

"article-title": "Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials",

"author": "Theodoratou",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "g2035",

"journal-title": "BMJ",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib9",

"volume": "348",

"year": "2014"

},

{

"article-title": "The \"sunshine\" vitamin",

"author": "Nair",

"first-page": "118",

"journal-title": "J Pharmacol Pharmacother",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib10",

"volume": "3",

"year": "2012"

},

{

"DOI": "10.3310/hta23020",

"article-title": "Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: individual participant data meta-analysis",

"author": "Martineau",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1",

"journal-title": "Health Technol Assess",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib11",

"volume": "23",

"year": "2019"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60404-8",

"article-title": "What makes UK Biobank special?",

"author": "Collins",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1173",

"journal-title": "Lancet",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib12",

"volume": "379",

"year": "2012"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779",

"article-title": "UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age",

"author": "Sudlow",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "e1001779",

"journal-title": "PLoS Med",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib13",

"volume": "12",

"year": "2015"

},

{

"author": "Armstrong",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib14",

"series-title": "Dynamic linkage of COVID-19 test results between Public Health England’s Second Generation Surveillance System and UK Biobank",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/ije/dym276",

"article-title": "Biobank UK. The UK Biobank sample handling and storage protocol for the collection, processing and archiving of human blood and urine",

"author": "Elliott",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "234",

"journal-title": "Int J Epidemiol",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib15",

"volume": "37",

"year": "2008"

},

{

"author": "Townsend",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib17",

"series-title": "Health and deprivation: inequality and the North",

"year": "1987"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1136/bmj.i6201",

"article-title": "Should adults take vitamin D supplements to prevent disease?",

"author": "Bolland",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "i6201",

"journal-title": "BMJ",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib18",

"volume": "355",

"year": "2016"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1007/s40615-020-00756-0",

"article-title": "The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities",

"author": "Laurencin",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"journal-title": "J Racial Ethn Health Disparities",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib19",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1152/ajpendo.00138.2020",

"article-title": "COVID-19 and vitamin D-Is there a link and an opportunity for intervention?",

"author": "Jakovac",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "E589",

"journal-title": "Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib20",

"volume": "318",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"article-title": "Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths",

"author": "Grant",

"first-page": "12",

"journal-title": "Nutrients",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib21",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"article-title": "Editorial: low population mortality from COVID-19 in countries south of latitude 35 degrees North - supports vitamin D as a factor determining severity",

"author": "Rhodes",

"journal-title": "Aliment Pharmacol Ther",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib22",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047659",

"article-title": "Obesity a risk factor for severe COVID-19 infection: multiple potential mechanisms",

"author": "Sattar",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"journal-title": "Circulation",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib23",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1001/jama.2020.6775",

"article-title": "Presenting Characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York city area",

"author": "Richardson",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"journal-title": "J Am Med Assoc",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib24",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"article-title": "Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease",

"author": "Liu",

"journal-title": "Chin Med J (Engl)",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib25",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"article-title": "Low incidence of daily active tobacco smoking in patients with symptomatic COVID-19",

"author": "Miyara",

"journal-title": "Qeios",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib26",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/aje/kwx246",

"article-title": "Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related Characteristics of UK biobank participants with those of the general population",

"author": "Fry",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1026",

"journal-title": "Am J Epidemiol",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib27",

"volume": "186",

"year": "2017"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0026",

"article-title": "Intraindividual variation in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D measures 5 years apart among postmenopausal women",

"author": "Meng",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "916",

"journal-title": "Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev",

"key": "10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050_bib28",

"volume": "21",

"year": "2012"

}

],

"reference-count": 27,

"references-count": 27,

"relation": {},

"resource": {

"primary": {

"URL": "https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871402120301156"

}

},

"score": 1,

"short-title": [],

"source": "Crossref",

"subject": [

"General Medicine",

"Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism",

"Internal Medicine"

],

"subtitle": [],

"title": "Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank",

"type": "journal-article",

"update-policy": "http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/elsevier_cm_policy",

"volume": "14"

}