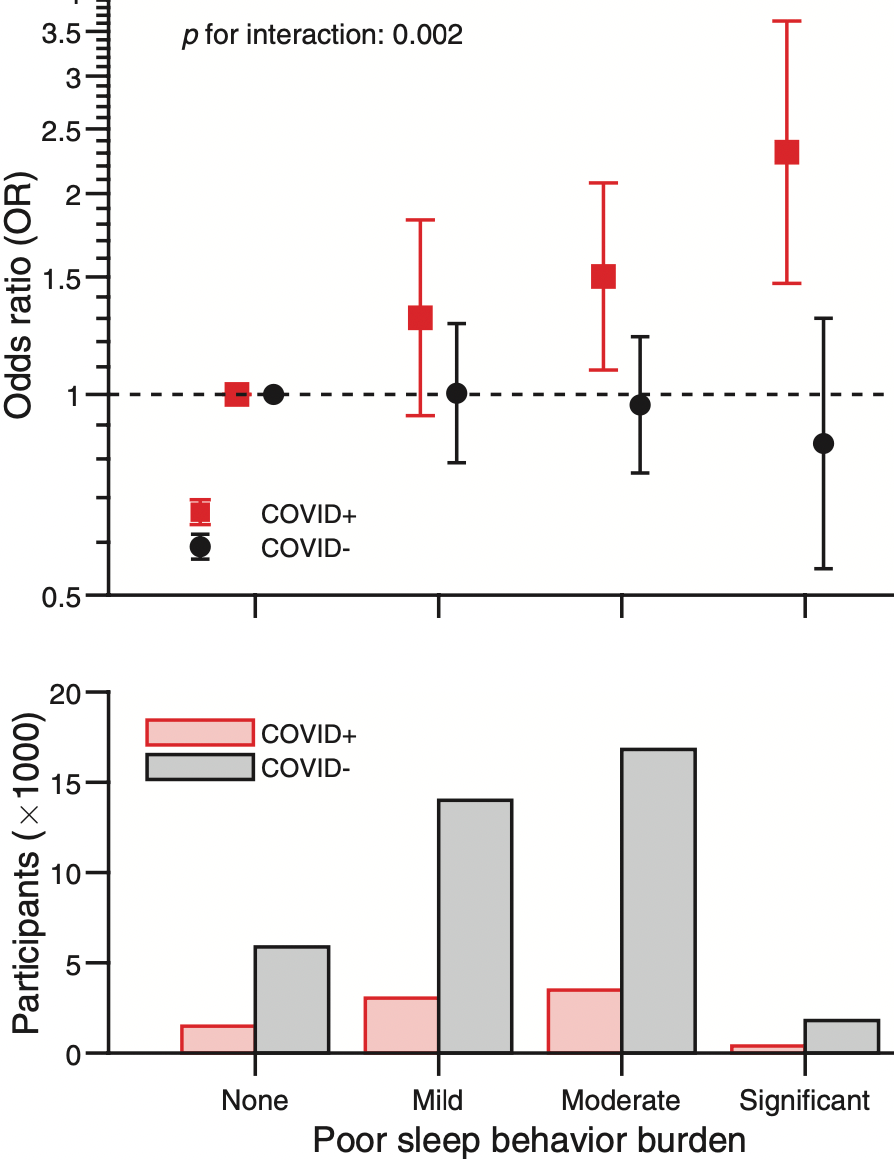

Poor sleep behavior burden and risk of COVID-19 mortality and hospitalization

et al., Sleep, doi:10.1093/sleep/zsab138, Jun 2021

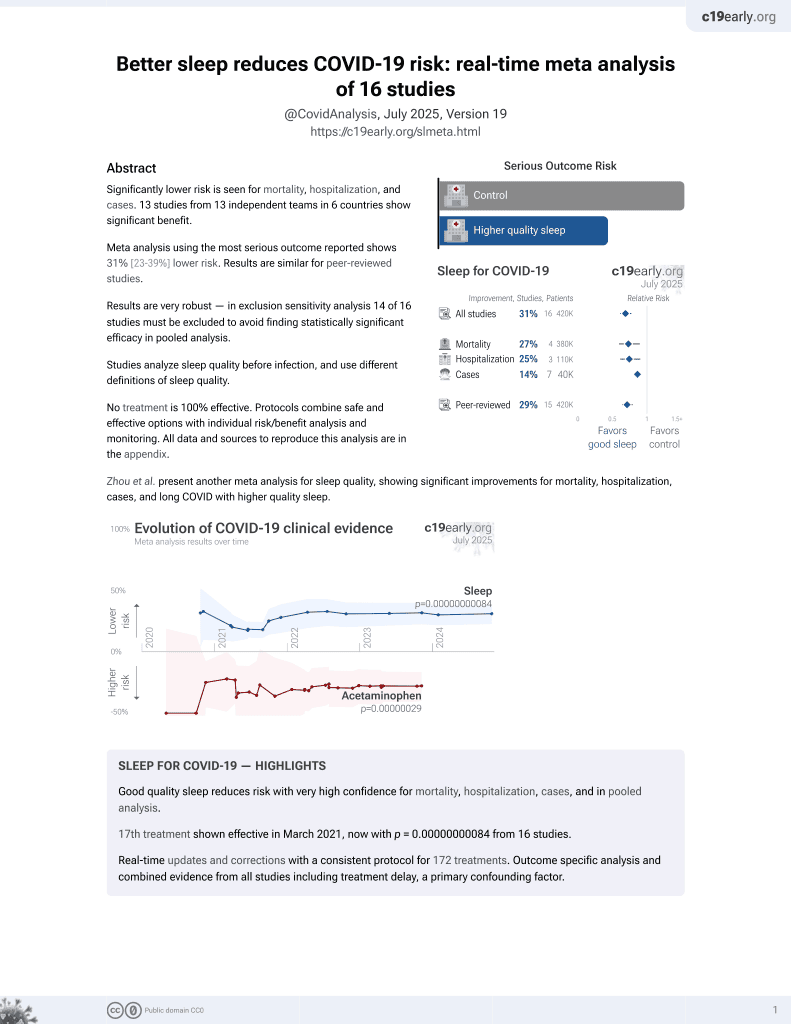

Sleep for COVID-19

18th treatment shown to reduce risk in

March 2021, now with p = 0.00000000084 from 16 studies.

No treatment is 100% effective. Protocols

combine treatments.

6,400+ studies for

210+ treatments. c19early.org

|

UK Biobank retrospective, 46,535 participants with sleep behavior assessed between 2006 and 2010, showing higher risk of hospitalization and mortality with poor sleep.

Standard of Care (SOC) for COVID-19 in the study country,

the USA, is very poor with very low average efficacy for approved treatments1.

Only expensive, high-profit treatments were approved for early treatment. Low-cost treatments were excluded, reducing the probability of early treatment due to access and cost barriers, and eliminating complementary and synergistic benefits seen with many low-cost treatments.

|

risk of death, 43.2% lower, OR 0.57, p = 0.02, inverted to make OR<1 favor improved sleep, fully adjusted model C, significant poor sleep burden, RR approximated with OR.

|

|

risk of hospitalization, 35.9% lower, OR 0.64, p = 0.008, inverted to make OR<1 favor improved sleep, fully adjusted model C, significant poor sleep burden, RR approximated with OR.

|

|

risk of hospitalization, 21.3% lower, OR 0.79, p = 0.02, inverted to make OR<1 favor improved sleep, fully adjusted model C, moderate poor sleep burden, RR approximated with OR.

|

| Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules prioritizing more serious outcomes. Submit updates |

Li et al., 18 Jun 2021, retrospective, USA, peer-reviewed, mean age 69.4, 8 authors, study period March 2020 - December 2020.

Contact: pli9@bwh.harvard.edu, khu1@bwh.harvard.edu, lgao@mgh.harvard.edu.

Abstract: SLEEPJ, 2021, 1–3

doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab138

Advance Access Publication Date: 18 June 2021

Letter to the Editor

Letter to the Editor

Peng Li1,2,*, , Xi Zheng1, Ma Cherrysse Ulsa1, Hui-Wen Yang1,

Frank A. J. L. Scheer1,2,3, , Martin K. Rutter4, Kun Hu1,2,3,*,†, and Lei Gao1,2,5,*,†,

Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s

Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, 2Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA, 3Medical

Chronobiology Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston,

MA, USA, 4Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology & Gastroenterology, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

and 5Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard

Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

1

Contributed equally.

*Corresponding author. Peng Li, Kun Hu, or Lei Gao, Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s

Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, USA. Email: pli9@bwh.harvard.edu; khu1@bwh.harvard.edu; lgao@mgh.harvard.edu.

†

Dear Editor,

Despite the unprecedented efforts in vaccinations, the COVID19 pandemic will likely continue to affect those most vulnerable [1], and the need to identify modifiable risk factors remains

[2]. Poor sleep behavior traits have been linked to multisystemic

disruptions [3], but whether this is linked to COVID-19 severity

remains unknown. Using, the UK Biobank, a population-based

cohort of >500 000 participants recruited between 2006 and

2010 [4], we determined the associations of poor sleep behavior

burden with mortality, and need for hospitalization after a positive COVID-19 result.

This study was restricted to 46 535 participants tested between March and December 2020 (age: 69.4 ± 8.3 years [mean ±

standard deviation]; female: 53.3%). Sleep behavior traits (duration, daytime sleepiness, insomnia, and chronotype) were assessed between 2006 and 2010. Scores of 0 (if sleep duration

between 6 and 9 h, “never/rarely” daytime sleepiness/insomnia,

or non-evening chronotype), 1 (if short <6 h, or long sleeper

>9 h, “sometimes” experience daytime sleepiness/insomnia, or

evening chronotype), and 2 (if “often/all the time” experience

daytime sleepiness, or “usually” have insomnia) were assigned,

and summed to obtain a sleep behavior score ranging from 0 to 6,

where higher scores are indicative of multiple domains of poor

sleep behavior traits. We used this to classify poor sleep behavior

burden as follows: “none” (0), “mild” (1), “moderate” (2–3), and

“significant” (4–6).

8422 participants tested positive (COVID+), defined as the

earliest result from PCR tests, provided by Public Health England.

If tested but never positive (COVID−; n = 38 113), the earliest test

date was used. Primary outcome was 30-day mortality, matched

to death registry dates. The interaction effect between sleep behavior burden and COVID positivity/negativity on mortality was

also tested.

Finally, hospitalization within 7 days of a positive test was

extracted by matching dates with hospital admission data (7146

positive cases available). We included test results that were reported up to 4 days after death or hospitalization, per the UK

Biobank’s guidance over testing-to-result time frames; thus, we

excluded 11 participants with a date of death and/or hospitalization more than 4 days before test results were released.

Logistic regression models were used to determine the..

DOI record:

{

"DOI": "10.1093/sleep/zsab138",

"ISSN": [

"0161-8105",

"1550-9109"

],

"URL": "http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab138",

"author": [

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4684-4909",

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Li",

"given": "Peng",

"sequence": "first"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"family": "Zheng",

"given": "Xi",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"family": "Ulsa",

"given": "Ma Cherrysse",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"family": "Yang",

"given": "Hui-Wen",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2014-7582",

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Medical Chronobiology Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Scheer",

"given": "Frank A J L",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology & Gastroenterology, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK"

}

],

"family": "Rutter",

"given": "Martin K",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0350-3132",

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Medical Chronobiology Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Hu",

"given": "Kun",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"ORCID": "http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1476-1460",

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Medical Biodynamics Program, Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA"

},

{

"name": "Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA"

}

],

"authenticated-orcid": false,

"family": "Gao",

"given": "Lei",

"sequence": "additional"

}

],

"container-title": "Sleep",

"content-domain": {

"crossmark-restriction": false,

"domain": []

},

"created": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

18

]

],

"date-time": "2021-06-18T11:10:02Z",

"timestamp": 1624014602000

},

"deposited": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

8,

13

]

],

"date-time": "2021-08-13T09:10:36Z",

"timestamp": 1628845836000

},

"funder": [

{

"DOI": "10.13039/100000002",

"award": [

"T32GM007592",

"R03AG067985",

"RF1AG064312",

"RF1AG059867",

"R01HL140574"

],

"doi-asserted-by": "publisher",

"name": "National Institutes of Health"

}

],

"indexed": {

"date-parts": [

[

2022,

4,

14

]

],

"date-time": "2022-04-14T20:28:25Z",

"timestamp": 1649968105746

},

"is-referenced-by-count": 7,

"issue": "8",

"issued": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

18

]

]

},

"journal-issue": {

"issue": "8",

"published-online": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

18

]

]

},

"published-print": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

8,

13

]

]

}

},

"language": "en",

"license": [

{

"URL": "https://academic.oup.com/journals/pages/open_access/funder_policies/chorus/standard_publication_model",

"content-version": "vor",

"delay-in-days": 0,

"start": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

18

]

],

"date-time": "2021-06-18T00:00:00Z",

"timestamp": 1623974400000

}

}

],

"link": [

{

"URL": "http://academic.oup.com/sleep/advance-article-pdf/doi/10.1093/sleep/zsab138/38692897/zsab138.pdf",

"content-type": "application/pdf",

"content-version": "am",

"intended-application": "syndication"

},

{

"URL": "http://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-pdf/44/8/zsab138/39624117/zsab138.pdf",

"content-type": "application/pdf",

"content-version": "vor",

"intended-application": "syndication"

},

{

"URL": "http://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-pdf/44/8/zsab138/39624117/zsab138.pdf",

"content-type": "unspecified",

"content-version": "vor",

"intended-application": "similarity-checking"

}

],

"member": "286",

"original-title": [],

"prefix": "10.1093",

"published": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

18

]

]

},

"published-online": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

18

]

]

},

"published-other": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

8,

1

]

]

},

"published-print": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

8,

13

]

]

},

"publisher": "Oxford University Press (OUP)",

"reference": [

{

"DOI": "10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32117-6",

"article-title": "Living with the COVID-19 pandemic: act now with the tools we have",

"author": "Bedford",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1314",

"issue": "10259",

"journal-title": "Lancet.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0001",

"volume": "396",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040402",

"article-title": "Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for COVID-19, and comparison to risk factors for influenza and pneumonia: results from a UK Biobank prospective cohort study",

"author": "Ho",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "e040402",

"issue": "11",

"journal-title": "BMJ Open.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0002",

"volume": "10",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/eurheartj/ehz849",

"article-title": "Sleep patterns, genetic susceptibility, and incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of 385 292 UK Biobank participants",

"author": "Fan",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1182",

"issue": "11",

"journal-title": "Eur Heart J.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0003",

"volume": "41",

"year": "2020"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779",

"article-title": "UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age",

"author": "Sudlow",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "e1001779",

"issue": "3",

"journal-title": "PLoS Med.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0004",

"volume": "12",

"year": "2015"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.014",

"article-title": "Sleep loss and inflammation",

"author": "Mullington",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "775",

"issue": "5",

"journal-title": "Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0005",

"volume": "24",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1093/sleep/33.12.1649",

"article-title": "Are inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers related to sleep characteristics in mid-life women? Study of Women’s Health across the Nation sleep study",

"author": "Matthews",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1649",

"issue": "12",

"journal-title": "Sleep.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0006",

"volume": "33",

"year": "2010"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1136/archdischild-2020-320338",

"article-title": "Why is COVID-19 less severe in children? A review of the proposed mechanisms underlying the age-related difference in severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections",

"author": "Zimmermann",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "429",

"journal-title": "Arch Dis Child.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0007",

"volume": "106",

"year": "2021"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1016/j.tem.2019.07.008",

"article-title": "Impact of circadian disruption on cardiovascular function and disease",

"author": "Chellappa",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "767",

"issue": "10",

"journal-title": "Trends Endocrinol Metab.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0008",

"volume": "30",

"year": "2019"

},

{

"DOI": "10.1001/jama.2016.4454",

"article-title": "Association between rotating night shift work and risk of coronary heart disease among women",

"author": "Vetter",

"doi-asserted-by": "crossref",

"first-page": "1726",

"issue": "16",

"journal-title": "JAMA.",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0009",

"volume": "315",

"year": "2016"

},

{

"article-title": "Shift work is associated with positive COVID-19 status in hospitalised patients,",

"author": "Maidstone",

"key": "2021081309083078800_CIT0010",

"year": "2020"

}

],

"reference-count": 10,

"references-count": 10,

"relation": {},

"resource": {

"primary": {

"URL": "https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/doi/10.1093/sleep/zsab138/6304657"

}

},

"score": 1,

"short-title": [],

"source": "Crossref",

"subject": [

"Physiology (medical)",

"Neurology (clinical)"

],

"subtitle": [],

"title": "Poor sleep behavior burden and risk of COVID-19 mortality and hospitalization",

"type": "journal-article",

"volume": "44"

}