Assessment of vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19 diagnosis in patients with breast or prostate cancer using electronic medical records

et al., Journal of Clinical Oncology, doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.6589, May 2021

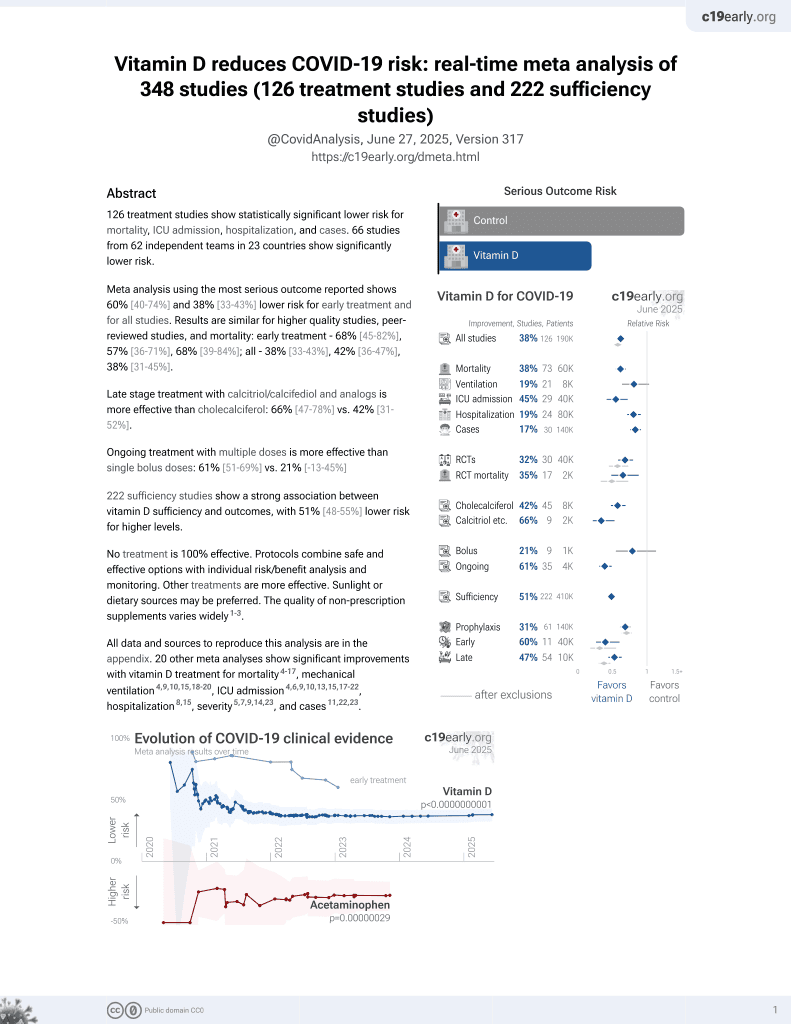

Vitamin D for COVID-19

8th treatment shown to reduce risk in

October 2020, now with p < 0.00000000001 from 136 studies, recognized in 18 countries.

No treatment is 100% effective. Protocols

combine treatments.

6,400+ studies for

210+ treatments. c19early.org

|

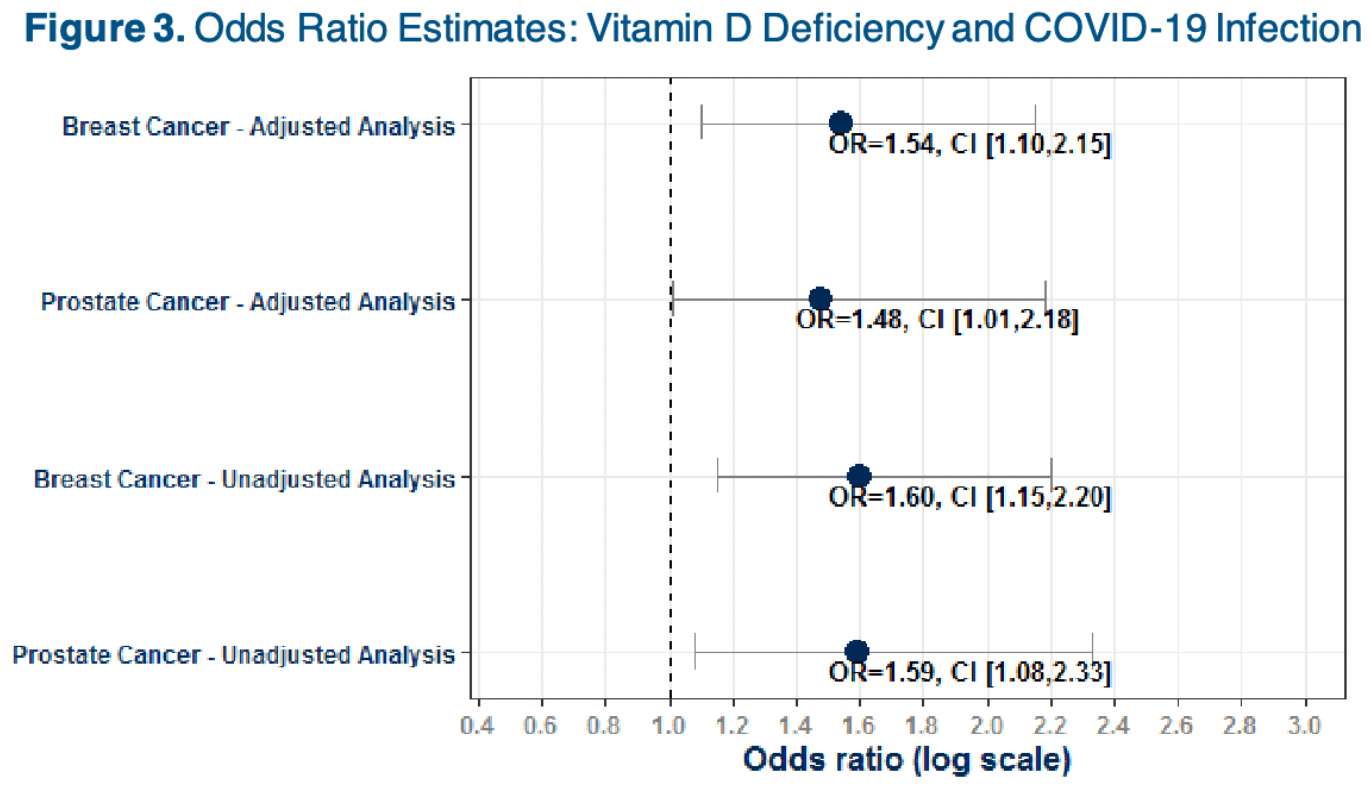

Retrospective 16,287 breast cancer and 14,919 prostate cancer showing increased risk of COVID-19 cases with vitamin D deficiency.

This is the 68th of 228 COVID-19 sufficiency studies for vitamin D, which collectively show higher levels reduce risk with p<0.0000000001.

Standard of Care (SOC) for COVID-19 in the study country,

the USA, is very poor with very low average efficacy for approved treatments1.

Only expensive, high-profit treatments were approved for early treatment. Low-cost treatments were excluded, reducing the probability of early treatment due to access and cost barriers, and eliminating complementary and synergistic benefits seen with many low-cost treatments.

|

risk of case, 35.1% lower, OR 0.65, p = 0.01, high D levels 13,903, low D levels 2,384, adjusted per study, inverted to make OR<1 favor high D levels, breast cancer patients, logistic regression, RR approximated with OR.

|

|

risk of case, 32.4% lower, OR 0.68, p = 0.045, high D levels 13,601, low D levels 1,318, adjusted per study, inverted to make OR<1 favor high D levels, prostate cancer patients, logistic regression, RR approximated with OR.

|

| Effect extraction follows pre-specified rules prioritizing more serious outcomes. Submit updates |

Galaznik et al., 28 May 2021, retrospective, USA, preprint, 6 authors.

Abstract: Assessment of Vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19 diagnosis in patients with breast or

prostate cancer using Electronic Medical Records

Aaron Galaznik, MD MBA1 | Emelly Rusli, MPH1 | Vicki Wing, MS1 | Rahul Jain, PhD1 | Sheila Diamond, MS CGC1 | David Fajgenbaum, MD MBA MSc FCPP2

1 Medidata Acorn AI, a Dassault Systèmes company, New York, NY, 10014 | 2 Castleman Disease Collaborative Network and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 19104

RESULTS

BACKGROUND

BACKGROUND

•

•

While patients with cancer are known to be at increased risk

of infection in part due to the immunocompromising nature of

cancer treatments, recent data indicate a particularly high

risk for COVID-19 infection and poor outcomes. 1

•

Our study suggests

potentially vulnerable

populations, such as breast

and prostate cancer

patients, may have an

elevated risk of

COVID-19 infection if

vitamin D deficient.

Vitamin D deficiency has been previously reported in two

leading causes of cancer deaths: breast and prostate. 4

•

In this study, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis on

nationally representative electronic medical records (EMR) to

assess whether vitamin D deficiency affects risk of COVID19 among these patients.

Vitamin D may play an important role in COVID-19. A recent

study demonstrated vitamin D deficiency may increase risk of

COVID-19 infection, and a small randomized controlled trial

in Spain reported significant improvement in mortality among

hospitalized patients treated with calcifediol. 2,3

METHODS

Figure 1. Study Timeline

•

A total of 16,287 breast cancer and 14,919 prostate cancer patients were included in the study. (Figure 2)

Table 1. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Breast Cancer

TOTAL (N = 16,287)

Patient Characteristics

N/Mean

%/SD

N/Mean

%/SD

68.9

11.3

73.6

8.5

<70 years (n, %)

7,962

48.9%

4,625

31.0%

70-79 years (n, %)

5,368

33.0%

6,499

43.6%

80+ years (n, %)

2,957

18.2%

3,795

25.4%

16,287

100.0%

0

0.0%

0

13,805

2,102

305

16

49

10

0.0%

84.8%

12.9%

1.9%

0.1%

0.3%

0.1%

14,919

12,390

2,405

89

12

22

1

100.0%

83.1%

16.1%

0.6%

0.1%

0.1%

0.0%

2,384

14.6%

1,318

8.8%

1.1

1.5

1.4

1.7

Congestive heart failure (n, %)

1,075

6.60%

1,483

9.94%

Obesity (n, %)

5,036

30.9%

4,627

31.0%

Diabetes mellitus (n, %)

3,327

20.4%

3,897

26.1%

356

2.2%

303

2.0%

1,730

10.6%

2,371

15.9%

Age (Mean, SD)

Sex (n, %)

Female

Male

White

Race (n, %)

Black

Asian

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

American Indian or Alaska Native

Missing

Vitamin D deficient (n, %)

Comorbid

Conditions

Quan Charlson Comorbidity Index (Mean, SD)

Liver disease (n, %)

Figure 2. Patient Attrition

Patient with ≥ 1 encounter

between 3/1/2018 and

3/1/2019, and after 3/1/2020

(index date)

Age ≥ 18 and non-missing sex

and race

n = 1,630,384 (52.8%)

•

•

•

Patients with breast (female) or prostate (male) cancer

were identified between 3/1/2018 and 3/1/2020 from

Healthjump EMR data provided pro-bono by the COVID-19

Research Database.5

Logistic regressions, adjusted for baseline demographic

and clinical characteristics assessed in the 12 months prior

to 3/1/2020, were conducted to estimate the effect of

•

•

The average age was 68.9 years in the breast cancer cohort

and 73.6 years in the prostate cancer cohort.

(Table 1)

•

Approximately 15% of the breast cancer cohort and 9% of

the prostate cancer cohort had vitamin D deficiency.

•

The most common comorbid conditions were obesity

(approximately a third..

DOI record:

{

"DOI": "10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.6589",

"ISSN": [

"0732-183X",

"1527-7755"

],

"URL": "http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.6589",

"abstract": "<jats:p> 6589 </jats:p><jats:p> Background: While patients with cancer are known to be at increased risk of infection in part due to the immunocompromising nature of cancer treatments, recent data indicate a particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection and poor outcomes (Wang et al., 2020). A recent study (Meltzer et al., 2020) demonstrated Vitamin D deficiency may increase risk of COVID-19 infection, and a small randomized controlled trial in Spain reported significant improvement in mortality among hospitalized patients treated with calcifediol. Vitamin D deficiency has been reported in two leading causes of cancer deaths: breast and prostate. In this study, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis on nationally representative electronic medical records (EMR) to assess whether Vitamin D deficiency affects risk of COVID-19 among these patients. Methods: Patients with breast (female) or prostate (male) cancer were identified between 3/1/2018 and 3/1/2020 from EMR data provided pro-bono by the COVID-19 Research Database ( covid19researchdatabase.org ). Patients with an ICD-10 code for Vitamin D deficiency or < 20ng/mL 20(OH)D laboratory result within 12 months prior to 3/1/2020 were classified as Vitamin D deficient. COVID-19 diagnosis was defined using ICD-10 codes and laboratory results for COVID-19 at any time after 3/1/2020. Logistic regressions, adjusting for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, were conducted to estimate the effect of Vitamin D deficiency on COVID-19 incidence in each cancer cohort. Results: A total of 16,287 breast cancer and 14,919 prostate cancer patients were included in the study. The average age was 68.9 years in the breast cancer cohort and 73.6 years in the prostate cancer cohort. The breast cancer cohort consisted of 85% Whites, 13% Black or African Americans, and less than 5% of other races. A similar race distribution was observed in the prostate cancer cohort. Unadjusted analysis showed the risk of COVID-19 was higher among Vitamin D deficient patients compared to non-deficient patients in both cohorts (breast: OR = 1.60 [95% C.I.: 1.15, 2.20]; prostate: OR = 1.59 [95% C.I.: 1.08, 2.33]). Similar findings were observed when assessed in subgroups of patients with newly diagnosed cancer in the dataset, as well as after adjusting for baseline characteristics. Conclusions: Our study suggests breast and prostate cancer patients may have an elevated risk of COVID-19 infection if Vitamin D deficient. These results support findings by Meltzer et al., 2020 demonstrating a relationship between Vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19 infection. While a randomized clinical trial is warranted to confirm the role for Vitamin D supplementation in preventing COVID-19, our study underscores the importance of monitoring Vitamin D levels across and within cancer populations, particularly in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic. </jats:p>",

"alternative-id": [

"10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.6589"

],

"assertion": [

{

"group": {

"label": "Publication History",

"name": "publication_history"

},

"label": "Published",

"name": "published",

"order": 3,

"value": "2021-05-28"

}

],

"author": [

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Acorn AI By Medidata, a Dassault Systèmes Company, New York, NY;"

}

],

"family": "Galaznik",

"given": "Aaron",

"sequence": "first"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Acorn AI By Medidata, a Dassault Systèmes Company, New York, NY;"

}

],

"family": "Rusli",

"given": "Emelly",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Acorn AI By Medidata, a Dassault Systèmes Company, New York, NY;"

}

],

"family": "Wing",

"given": "Vicki",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Acorn AI By Medidata, a Dassault Systèmes Company, New York, NY;"

}

],

"family": "Jain",

"given": "Rahul",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Acorn AI By Medidata, a Dassault Systèmes Company, New York, NY;"

}

],

"family": "Diamond",

"given": "Sheila",

"sequence": "additional"

},

{

"affiliation": [

{

"name": "Castleman Disease Collaborative Network and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA;"

}

],

"family": "Fajgenbaum",

"given": "David",

"sequence": "additional"

}

],

"container-title": [

"Journal of Clinical Oncology"

],

"content-domain": {

"crossmark-restriction": true,

"domain": [

"ascopubs.org"

]

},

"created": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

2

]

],

"date-time": "2021-06-02T14:28:38Z",

"timestamp": 1622644118000

},

"deposited": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

6,

3

]

],

"date-time": "2021-06-03T17:38:14Z",

"timestamp": 1622741894000

},

"funder": [

{

"name": "None"

}

],

"indexed": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

12,

16

]

],

"date-time": "2021-12-16T01:13:47Z",

"timestamp": 1639617227727

},

"is-referenced-by-count": 0,

"issn-type": [

{

"type": "print",

"value": "0732-183X"

},

{

"type": "electronic",

"value": "1527-7755"

}

],

"issue": "15_suppl",

"issued": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

5,

20

]

]

},

"journal-issue": {

"issue": "15_suppl",

"published-print": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

5,

20

]

]

}

},

"language": "en",

"member": "233",

"original-title": [],

"page": "6589-6589",

"prefix": "10.1200",

"published": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

5,

20

]

]

},

"published-print": {

"date-parts": [

[

2021,

5,

20

]

]

},

"publisher": "American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)",

"reference-count": 0,

"references-count": 0,

"relation": {},

"score": 1,

"short-container-title": [

"JCO"

],

"short-title": [],

"source": "Crossref",

"subject": [

"Cancer Research",

"Oncology"

],

"subtitle": [],

"title": [

"Assessment of vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19 diagnosis in patients with breast or prostate cancer using electronic medical records."

],

"type": "journal-article",

"update-policy": "http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/crossmark",

"volume": "39"

}